It all comes down to dirt

Not long ago, our local elementary school hosted a “Getting to Green” community event. My job was to work with my friend, Edie, an Audubon educator and farmer, to entertain the little ones while their parents listened to Dr. Halina Brown talk about “sustainable” consumerism.

Edie and "Clucky"

Edie, a spry elder with a twinkle and lightning-white hair, brought one of her chickens for the children to touch and hold. I brought one of my “systems playkits”.

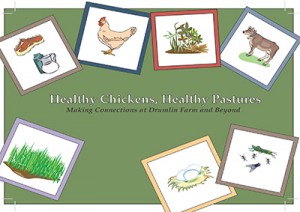

"Healthy Chickens, Healthy Farms" Playkit

“Clucky”, Edie’s barnyard bantam, was a huge success. The children, ranging in age from 3 to 8, sat cross-legged in a circle, listening intently as she explained why a chicken has this part and that, what they eat, what color eggs they lay (Thoreaucana, a breed Edie developed, lays greenish-blue eggs. Dr. Suess would approve).

Each child had a chance to feed and hold the chicken on their lap. To their great delight, they all received a white feather to stroke and tuck into their pockets to take home. When Edie finished, one of the monitors arrived to give the group a choice: “You can play basketball in the gym, or you can play a ‘systems game’ with Mrs. Sweeney.”

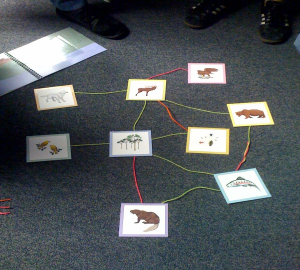

No surprise. Most of the children bolted to the gym! (Note to self: Drop the word “system” next time). The few who remained gathered into a small circle on the floor. I showed them pictures of a chicken coop at Drumlin Farm, a local Audubon site. We laid out playing cards with pictures of chickens, cows, grass, manure, insects, decomposing soil, eggs, people, the sun, and more, and gave everyone a handful of wikki stixs, bend-able sticks made from hand-knitting yarn enhanced with non-toxic wax. We were ready to play.

When they looked closely at the mobile coop they could see that this coop was unique: It had wheels!

The Egg Mobile, Drumlin Farm (Lincoln, MA)

“Now, why would that be?” we wondered. Lilly, a bright and curious first-grader, had been to Drumlin Farm. She’d seen the chickens scratching the grass near the mobile chicken coop. “I know, I know!” she said. “The chickens eat the bugs in the grass!” Lilly grabbed a green wikki stix and connected chicken card to the grass card.

I asked more questions: What happens to the chicken manure when it’s left in the field? How are the chickens, the pasture and people connected?

A group of children created this "systems map" using wikki stix (from the Wolves in Yellowstone playkit)

Then the group set to work, adding and taking away links. When they were done, they had “connected the dots”, and had put together a tightly linked “map” of causes and effects. They discovered that the more the soil was fed the chicken manure and decaying plants, the healthier it was. With a little help, they also saw the positive influence the chickens had on the health of cows (eating the harmful insect larvae in the cow’s manure), people (an omnivore’s diet improved the quality of the chicken’s eggs) and the climate (less fossil fuels needed to produce chicken feed)

When the last wikki stix was pressed into place, Lilly paused to study the map. Then she exclaimed: “It all comes down to dirt!”

If you read the newspapers, you know that this statement is both timely and profound. Loss of topsoil and soil erosion due to over-farming and over-grazing of fragile soils is, according to The Worldwatch Institute, “A quiet crisis in the world economy.” The causes of soil erosion (expanding demand for food, short-cut farming practices) and consequences (silt-laden rivers, desertification) are complex. Said simply though, the more the soil erodes, the less productive it is. Without good topsoil, plants cannot grow.

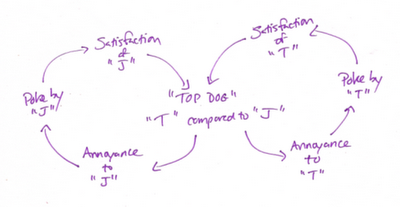

So, Lilly, at the tender of seven, got it. She explored the interconnections and dynamics of the farm and found that all roads (all wikki stix in this case) lead to the soil. In just a short half hour, she discovered the role soil plays in the health of crops, animals and people. With more time, she would have also likely discovered soil’s role in the cleanliness of water and the livelihoods of farmers. She might also have been guided to think about “systems” as an organizing framework to take home and apply, for instance to that escalating squabble with her brother or to preventing homework “burn-out.”

So, Lilly, at the tender of seven, got it. She explored the interconnections and dynamics of the farm and found that all roads (all wikki stix in this case) lead to the soil. In just a short half hour, she discovered the role soil plays in the health of crops, animals and people. With more time, she would have also likely discovered soil’s role in the cleanliness of water and the livelihoods of farmers. She might also have been guided to think about “systems” as an organizing framework to take home and apply, for instance to that escalating squabble with her brother or to preventing homework “burn-out.”

Systems Playkits, like the one I used with Lilly and her friends, have been used on farms, in public workshops, with a local girl scout troop towards earning their eco-explorer badge, and most recently with a group of 50 graduate students, studying sustainable development and education in Brazil.

Students in the Post Graduate Program on Integral Sustainability at The Instituto Visão Futuro (Brazil, 2011)

People, whether they’re eight or 88, like to touch, build, discover, explore, imagine and play. Using all their senses and interacting with the real world increases the depth and breadth of learning. As our children begin to understand the critical issues that shape our interdependent world, let them become true “systems citizens” with their hands in the dirt and a chicken feather in their pocket. I think Confucius had it right when he said:

When I hear, I forget,

When I see, I remember,

When I do, I understand.

About the Systems Playkit:

Working with the Creative Learning Exchange and Drumlin Farm, we designed the “Healthy Chickens, Healthy Pastures” playkit to encourage students to think deliberately about living systems in a farm setting. Through observation and play, the students discover the often hidden connections within the pasture and see the people, and wildlife around the farms, not as a set of interesting but disconnected parts, but as components in a vibrant living system. When used in educational settings, the game also provides students with an organizing framework (informed by system dynamics) to take home and apply in other contexts. (The “Healthy Chickens, Healthy Pastures” playkit can be ordered through the Creative Learning Exchange).

An Opportunity to Learn and Play with Systems

Want to learn more about systems? Check out Camp Snowball in Tucson the week of July 21-25. This summer “camp” experience brings together students, parents, educators, and business and community leaders to build everyone’s capacity for learning and leading in the 21st century. Teams and individuals from school systems and communities around the world are invited to learn how to enable youth to develop into “systems citizens.”

Many thanks to my good friends Gale Prior and Sara Schley for your thoughtful comments on this article. And to Ann Jennings (superb graphic designer), Renata Pomponi (Drumlin Farm) and Lees Stuntz (CLE) for our most enjoyable and fruitful collaboration!